Pushing Boundaries with Dr. Thomas R Verny

Pushing Boundaries with Dr. Thomas R Verny

Exploring the Art of Persuasion with Michael McQueen

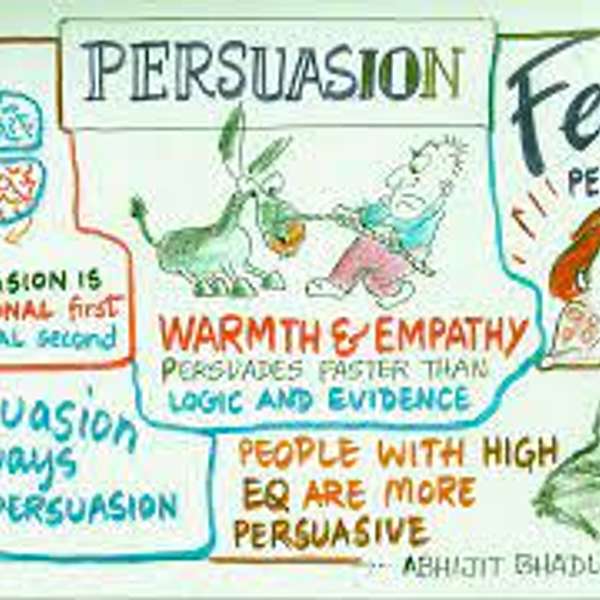

Promise one thing: by the end of this conversation with bestselling author and professional speaker, Michael McQueen, you'll have an entirely new perspective on open-mindedness and persuasion. We embark on a deep exploration of the human mind, uncovering the psychology behind stubbornness and taking a fresh look at the art of ethically influencing others. Michael, renowned for his insightful perspectives, shares critical nuggets from his book, Mindstruck: Mastering the Art of Changing Minds, and discusses how we can become more open-minded and encourage others to do the same.

As we navigate this fascinating discussion, we compare modern persuasion techniques with principles from Dale Carnegie's classic, How to Make Friends and Influence People. There's a unique focus on the importance of allowing people to maintain their dignity during persuasion, a strategy that has proven beneficial for large companies like Pepsi and KPMG. We'll also dive headfirst into the seismic changes witnessed in the automotive industry due to the pandemic and the intricacies of leading a team in a remote or hybrid environment.

Lastly, we take a journey through the generational labyrinth of the workplace, highlighting the impact of social and technological transformations. We'll touch on the art of effective communication and the power it holds in shaping future thinking. So, gear up for an episode packed with insights that will challenge your perception, redefine your understanding of persuasion, and equip you with the tools to navigate the rapidly evolving professional landscape. Get ready to change minds and perspectives, including your own.

If you liked this podcast

- please tell your friends about it,

- subscribe to this podcast wherever you listen to podcasts and/or write a brief note on apple podcasts,

- check out my blogs on Psychology Today at

https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/contributors/thomas-r-verny-md

Good morning in Australia, good evening in Canada. This is Pushing Boundaries, a podcast about pioneering research, breakthrough discoveries and unconventional ideas. I'm your host, dr Thomas R Birney. My guest today is Michael McQueen, a Sydney-based social researcher, professional speaker and bestselling author of eight books. Is it eight or is it more?

Speaker 2:This is that one. The new one clicks over 10. So, yeah, it's like that's sort of rack up. Yes.

Speaker 1:Okay, 10. I'm going to correct that of 10 books, okay. And with clients, he has had some incredible clients, including KPMG, pepsi Cola and Cisco. He has helped some of the world's most successful brands navigate disruption and maintain momentum. In addition to featuring regularly as a commentator on TV and radio, michael is a familiar face on the international conference circuit, having shared the stage with the likes of Bill Gates, dr John Maxwell and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak. I bet you have some interesting stories about that. Indeed, michael has spoken to over 500,000 people across five continents since 2004. Having been formerly named Australia's keynote speaker of the year, michael has been inducted into the Professional Speakers Hall of Fame. Welcome, michael.

Speaker 2:Thank you so much and thank you for making the time. Lovely to be able to have a chat on air We've been back in fourth via email but lovely to put a proper face to the name and the voices. Well, thank you.

Speaker 1:Your most recent book, mindstruck Mastering the Art of Changing Minds, serves up a multitude of facts and insights about how to help yourself to become more open-minded, but also about how to influence other people. Now, am I getting that mixed up about the open-minded about another book, or is that? No, that's exactly it. Okay, yeah, all right, so why don't we start there? So perhaps you could talk a little bit about what set you on writing this book and give us a nutshell idea of what it's about.

Speaker 2:Yeah. So the book's all about essentially the psychology of stubbornness, and that's a two-way deal. That's why are we stubborn Now? Why do we get locked in certain ways of thinking that aren't serving us well? But also, why do others get locked into certain ways of thinking that are not constructive or helpful? And I guess the question that drives the book in many ways is why don't people change, even when they want to and they know they should? And then how do you try and, in an ethical way, with integrity and with their best interest in mind, help other people change their perspective and change their minds? So the notion is quite, I guess, calling a new word, Mindstuck, this idea that we get Mindstuck as human beings. Then how do you get out of that state?

Speaker 1:Mm-hmm, okay, so I think what you try to do is persuasion without coercion.

Speaker 2:That's the goal, because there are so many books and I mean you ought to come across so many of them over the years as well and I understand that they want to be intensely practical and useful. But a lot of those books that I can think of a number right now that actually, if you really take the tips and the principles in them to the extreme, they are tools of manipulation or coercion. Yes, even some of the NLP, neuro Linguistic Programming stuff. It's just been a bit uncomfortable to me. It always feels a little bit underhanded. You're trying to get someone to do things in a way that's tricky or conniving, even if it's not intended to be that. So I wanted to write a book that was quite different. So the purpose of this book is how do you arrive at points of truth together with others?

Speaker 2:I think, if that's one thing that we've lost the ability to do in the last few years and we've, of course, lived through the last five or six years that have been intensely tribal, where people have looked at the world through the lens of identity. Often, rather than asking the question of what is true, we'll ask questions of what are? People like me think about something like this, people from my tribe. And so, rather than actually evaluating or considering ideas, we often run straight to that sense of you know you're either with me or for me and anyone that I know whose side of an issue you're on. Then I'll listen to what you've got to say. And so how do we arrive at those points again where we can listen to each other and learn from each other? And, ideally, if you're wanting to persuade someone else in your world and it can be in family context or at work how to do that successfully but without being coercive or manipulative, and there is a fine art to doing that well.

Speaker 1:So how do you do it?

Speaker 2:Give us a few examples the first thing is, if you're looking at, say, stubbornness within ourselves, and it is ideally a book that looks at both. The first thing I'd encourage anyone to do and I actually had this very experience yesterday where I was like I need to. You know, we've got to consistently learn from our own stuff, you know, like make sure we're applying what we're researching and writing to ourselves. And I think the first thing would be reflect on your reactions. And when you notice yourself have a reaction to an idea or a perspective that is not open, and you know what that feels like. We all know what that feels like when the hackles go up on the back of your neck and you go into flight mode. You want to argue or debate. Now Andy Stanley, who's a leadership author based in the States, puts it really well. He says actions speak louder than words, but reactions speak louder than both. I think there's such truth in that, like when you notice yourself having one of those strong reactions, a disproportionately strong reaction, big, a little bit beneath that. What's what's actually going on here? And a lot of the research I found interesting in the book was understanding how our brains are, our minds, and the difference between those two. I mean I'd love to unpack with you for an hour because I found your book in that regard fascinating. But if we just look at this idea of cognition alone for the moment, like what happens in our brains I'm Drew Weston at Emory University did some really interesting research a few years ago where he looked at response times or processing times, using brain scans, of where people were exposed to different ideas or bits of information.

Speaker 2:So what he found, which was interesting, is that if the information someone was exposed to, confronted or challenged a deeply held belief, it was attached to their identity, be it religious or political or even just ideological. In the workplace, their reaction times were fractional, like almost instant reactions, whereas if you promote, if you provided them with content that was related to something that they had no great attachment to maybe a new way of understanding sunscreens or the manufacturing process of yogurt their response times are forming an opinion about that were much slower. And what became very clear is that we are actually curious when it comes to new informational ideas that don't threaten us, but the moment there's a threat involved to our beliefs, it's like the reaction times and what became clear is we don't even consider them, we just instantly go to a default of react. So I think that's the first thing for all of us is when we notice that in ourselves or with others, to notice what's actually happening behind the scenes and also in that moment of asking okay, who's your brain rooting for right now? I mean, in Australia we use the term barracking, which, if your team's on the sports field, you're rooting for your team, you're barracking for your team. Same sort of concepts, and I think we we see that happen when it comes to ideas, even when we think we are super open minded.

Speaker 2:There's one side of a debate that deep down and you feel you know when it's happening. When someone in that debate from from your side, you don't even know you've got a side yet. Or when your side scores a point, he makes a point that could win the argument you're like yes, you know you and you'll accept it without any evidence because it confirms what you believe to be true. Whereas when, of course, the opposing team something you don't like scores a point or makes a good case, you instantly go into, are you trying to pick holes in it? And we so naturally do this. So a lot of, a lot of the book looks at why that happens, why we arrive at points of certainty and judgment. What happens in our brains now might do that, but also then, how do you shift people out of that?

Speaker 1:So all of that sounds really good. The problem, as I see it, the problem with books like yours and mine is that the people who picked them up are already halfway there. Yes, yeah, Okay, and you know, your book is not going to be picked up by one of the proud boys in the United States, right? People who are really what you call stubborn, which I think is very tactful and diplomatic, but essentially people with closed minds are not going to pick up your book and read about it. And so how do you talk to people who have already chosen sides and believe in all the conspiracy theories? For example, how do you get them.

Speaker 2:That's probably. Conspiracy belief is one of the most difficult, because the influence, of course, of algorithms means that by the time you've gone down that rabbit hole and fully subscribed to a conspiracy belief, you've not just attached a new identity yourself for someone who believes that thing, but you've attached an entire new community, and your community of fellow believers is defined by the fact that you're separate from the majority and you've got the other keepers of knowledge that the mainstream don't have, and so that, of course, is very difficult to break, because changing someone's mind when they've gone fully down that rabbit hole of conspiracy belief means not just walking away from a belief but walking away from their community, but also walking away from their sense of security that comes from, I know, something that everyone else is privy to, knowledge that everyone else doesn't have. So conspiracy belief is really challenging. So Josh Compton has done some good work around how to pre, bunk or inoculate people against conspiracy belief, and he's probably so. Him and a guy named Sandra Vanderlinden have done probably the best work in this regard, and they say the best way to prevent people from going down the rabbit hole is to essentially expose into a diluted form of misinformation, give them the tools to process it and understand it and, essentially, fight it. Much the way our bodies respond when we have a vaccine or an inoculation and therefore, when they're exposed to the real version, they know what to do. And so if you can get to people when they're in the early stages of conspiracy belief, for instance, that's helpful when they've gone right down the rabbit hole.

Speaker 2:The only thing I've found useful so far in terms of looking at the research of what works and what doesn't, is a thing called paradoxical thinking, which seems so strange, but it's a model, and I can't even remember where it came from now, which university and which researcher did it, but the idea was you expose someone to a more extreme version of the belief they hold and in doing so, create contrast. So, for instance, right now we've got a referendum happening in Australia around recognizing our First Nations people in the constitution, and it has gotten so messy. It's gotten right versus left, conservative versus progressive, what should have been, and I honestly, when it was launched as a referendum, I thought this will be a unanimous thing. It seemed like a really good idea and it's gotten so tense. So I'm speaking to people who are like if we give the indigenous people a voice to parliament, which is what the referendum is about. They'll take back our land, our homes, we'll have to fill in our swimming pools and there's no basis for any of that. But this is what people who've gone down that extreme level think. So when you've got someone, let's say who's saying I don't want to vote for this in the referendum because I don't like the idea of giving people a voice if we don't have clear checks and balances in place. If you can expose them to a more extreme version, I go. Yes, I know I get it. I get the concern.

Speaker 2:There are even people who have this fear that and then give the expose them to a more extreme version of their belief. Their first reaction is like oh, I would never say that, I'd never go that far. And even by creating the contrast between a more extreme version of what they believe, you break it up. You're breaking the soil up just enough for them to think is it possible? My view is a bit the same.

Speaker 2:Not based on anything that's reasonable or logical. It's not going to win the argument, but at least it tilts the soil and allows you to have a conversation. The tricky thing in that and it's, of course in any persuasion technique is you've got to allow them to save face. The moment people feel even that hint that they're cornered or shamed, I'll shut down. And I think one of the most helpful things I've kept in front of mind as I've written the book is this notion that everyone, everything that anyone thinks, makes perfect sense to them, like even the most ludicrous thing they think. How could you possibly think that in their mind? They've got a narrative which means it makes sense, and so I've got to start with and go okay, but make sense to them. Shaming or trying to logicfully them into changing their view is the opposite of what's going to work.

Speaker 1:That's good, that's smart. Yeah, you're absolutely right. You're absolutely right. So everybody knows, I guess, by now, Dale Carnegie's how to Make Friends and Influence People in 1936. So how does your book differ from that?

Speaker 2:I guess it's a good point because in many ways, when I started off writing this book, someone said what's your vision for this book? And I thought I guess it's quite grandiose really when I think about it. But I said I'd love to write the how to Make Friends and Influence People of the 21st century. I'd love to write a book that is really practical and useful across a huge cross-section, and that was the. I mean, the genius of that book is that it was really good for people who were in work contexts or family contexts and in so many different ways you could use it. And I wanted to write a book that was like that, because in the persuasion space there's a lot that's written with advertisers in mind or sales people in mind or maybe leaders in mind. But I wanted to write something that, if you're a mum of a 16 year old and you just you're trying to get your 16 year old to get off the screen or engage in homework or make better choices, it would be useful for you, as it would be in that.

Speaker 2:So I really wanted to write a book that was similar.

Speaker 2:In that sense, I think the big difference between what I've produced with mine stuck and say how to Influence People is Dale Carnegie was right about so much, but no one knew why there were.

Speaker 2:There was so little science at the time as to why people, why the things he suggested worked, and so the beauty is, I wanted to write a book that didn't just look at how to change people's minds and encourage people to become more open minded, but look at why the stuff that works actually works. What's what's happening in our brains and, more broadly, that means these things are effective because it's stuff that we just didn't know in 1936. So I wanted to bring together really practical and also timeless principles, but pair them up with really recent research and some of the research I've come across from people like you, from people like your book. To me it put language around so much that I'd been thinking and trying to pin down and you know, when you read a book you're like yes this is exactly what I've been trying to define or describe, so there's a few books like that that were just very helpful.

Speaker 2:So I wanted to bring all of that stuff together and make it very accessible to again, a mum with a 16 year old right through the leader of a corporate team.

Speaker 1:Okay, I can understand. That Makes a lot of sense. What do large companies like Pepsi or KPMG? How do they benefit from your advice? What do you tell them? What are they asking?

Speaker 2:Yeah, the big thing, the question this is a big part of why I wrote the book is that when I'm working with these sorts of clients and it can be the clients that listeners would know, but a lot of them, a lot of my clients are not known. They're like a government department responsible for policy development, for instance, and they're facing the same sorts of challenges that a Fortune 500 brand is facing, but they're just not as high profile. And I think for any leader right now, the challenge is how do you change your people in a way that lasts? Because you can try and encourage change through incentivizing or through threats of punishment, like do this or else, and that change will only last as long as either the incentives are there or the threat of punishment exists. The moment those things disappear, people just go back to the way they were doing it, and so a lot of my work over the years is the frustration I've seen is I'll work with, let's say, a leadership team around now.

Speaker 2:What's coming in the next three to five years from a disruption and trends perspective? What do you need to be doing to getting ready for it? And these leaders will go. Okay, I get it. I can see now what we need to be doing. How do I get my team on board? Or I'm speaking to someone okay, I get this, but I've got to influence up. I've got to get my executive team to be open to this as an idea.

Speaker 2:So what I've wanted to do with this book is essentially answer that question of okay, it's one thing to arm clients with the skills for knowing how to adapt and change and stay relevant, which I've been doing for two decades basically now but I wanted to also give them the tools to bring others along for the journey willingly, as opposed to you must, because I'm the boss and I said you've got to. And so that's where I wanted to really address that gap, because that's the question I would get literally day after day after day from clients is I get what needs to happen, but I can't seem to get my team to come on the journey and do so willingly. They're stuck, they're often fixed in very stubborn views.

Speaker 1:So a couple of years ago, speaking of that, you released a digital book called the new now, which examined the 10 trends that you thought will dominate a post COVID world and how leaders and organizations can gear up to them. Can you tell me a few of those 10 trends? What do you see happening?

Speaker 2:Well, I think yeah, I mean that book was really. Essentially it built on a book that came out pre COVID. Looking at the disruptions that we're going to shape the next few years. What we saw in the COVID years is we saw and the best way I had to describe was it's like we saw the future arrive ahead of schedule and it did in so many ways, things that we thought were five or 10 years away as trends happened in 18 months because of the pandemic. So that book was essentially an update in many ways and stuff that I've been tracking for a couple of years, but the things that were happening now in real time. So, obviously, the shift toward e-commerce rapidly accelerated when lockdowns meant that people had to use online services or click and collect in ways they hadn't used before. So we've seen the grocery market change rapidly over the last few years.

Speaker 2:Look what's happening in the automotive space with, say, self-driving car technology.

Speaker 2:Again, the pandemic meant that regulators actually gave the green light for some of those tests to be fast tracked because they realized the risk was you had all these human drivers driving around people and spreading COVID, and so we saw states like Arizona and California give the green light for driverless car technology to become a reality, honestly, six or seven years ahead of when we thought it would be.

Speaker 2:And so we've seen so many of those sorts of things that have come to the fore in ways that we just we thought were a long way off but have happened more quickly. And so I guess the challenge for many of my clients now is they're realizing the world is changing fast and now they've got to figure out how to get ready for it and gear up quickly without losing that sense of who they are. And one of the big things we've seen, of course, throughout the pandemic and it's lingering to today, is the shift towards remote and hybrid work, which is so difficult. Because how do you, if you're a leader, how do you build a team and build a team culture where people aren't necessarily around each other all the time?

Speaker 2:How do you influence or persuade people who you don't know, who you haven't got that sense of social credit with because you've not worked with them and know their families and know their backstory and what sports they're interested in? And so I think that's the tricky thing I'm finding now is we've seen that remote work and hybrid work thing become the default in many of my client organizations, and how do you lead that sort of a team and build culture? That's a very tricky question, because culture is caught, not taught. You pick up culture by being around other people in a team in a remote or hybrid environment. It's difficult, you can do it, but it's difficult to build that sort of culture.

Speaker 1:So how would you do it? What sort of advice do you proffer?

Speaker 2:How do you? Yeah, for leaders who are tinkering with this, who are realizing they've got these dispersed teams, first thing is you've got to have intensive times. When you bring people together, there is literally no substitute for being physically in the same location. That doesn't mean you have to do what's a sales force or Twitter or Meta or any of these other companies have done in the last three or four months, which is like you've got to come back in three days a week, mandatory. And you notice, of course, the moment that happens, everyone pushes back. You can't tell me. I mean, in itself is fascinating.

Speaker 2:Imagine if we'd said that back in 2019, that everyone was going to push back at you, daring to ask them to come back to the office three days a week. Imagine that. So, rather than having that, maybe it's, and you see a few companies that'll have what they call core weeks in the year. So there might be two-week blocks where you want everyone in the office five days a week, and that only happens maybe once every three months, and the beauty is, in those times you build the relationships, you build those strong connections, or you have team off-site events once a quarter. So, instead of having a conference where you gather the team together for one day at the Hilton Ballroom in a windowless space where you're all sitting listening to five speakers, having an off-site where you build those relationships.

Speaker 2:The other thing I'm finding really helpful for clients is, if you're having new staff kicking off, for the first two or three weeks have them in the office full-time so they get that feel for who's who and how things work. And then they can over time, by degrees, start working remotely more. But you've got to get them, you've got to have them feel connected out of the gate. If they don't have relationships, they don't feel connected, if far less engaged, far less connected to purpose, the organization's purpose, and they're also far less likely to stick around. Loyalty is a function of relationships in so many instances, particularly with younger generations, so having that sense of strong connection and social connection at work is really important.

Speaker 1:Yeah, that makes sense. So I think you mentioned the fact that for the last 20 years you have been working in this area. Is that correct? Yeah, that's correct.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:So how did you get into it to begin with?

Speaker 2:Yeah, so well.

Speaker 2:Firstly, I was young, I was 22 when I started doing this work, and so obviously I was not working with Fortune 500 companies and doing strategy days at the age of 22.

Speaker 2:Where I started was looking at the generation gap from the perspective of one of the young punks, one of the young people that everyone was talking about, which was that millennial cohort Right. So back in 2004, when I started doing the work I was doing in late 2003, it was like everyone was talking about the baby boomers versus Gen X versus the millennials. Why were we different? How much of the differences were substantive as opposed to a function of life stage? And then how do you bridge those gaps? And so I did a body of research, starting back in 2003, 2004, interviewing and working with 80,000 young people right around the world, looking at what's making them tick, what are their expectations around the workplace, and then I sort of condensed all that together into a book, looking at how organizations and leaders could engage their emerging workforce. So that's where I started, initially all around generational change, and how do you sort of gear up for that? And then the scope broadened to look at not just generational change but social change, technological change and then the trends all associated with those things.

Speaker 1:So was that like part of your PhD thesis, or what?

Speaker 2:It wasn't. So I did an undergraduate degree straight after school just in commerce, and then went from that and all of the research I've done since has been out of personal interest or stuff that I think will be useful for clients. So that research project I mean it was a very thorough piece of work I probably should have done as part of a PhD. It would have been sensible to kill two birds with one stone, but I just did it out of interest and based on what I was seeing as the trends as they formed in young people, but also what clients were asking for, what were the pain points for organizations and then trying to plug those or at least solve them. So that's typically been the focus for me.

Speaker 1:So how did you finance that? Like, how could you interview 80,000 people on your own?

Speaker 2:Good question. So well, firstly, bootstrapping and being young and not having a mortgage in kids that helps.

Speaker 2:So, it was. So initially what I did is I put together a program of essentially seminars for year, what we call Year 10 students, so in Australia, year 10 to age 16. So the last two or three years of high school. And so we'd run these programs, initially just in Sydney, where it was home for me, and then nationally and then overseas as well, and they were all around the school to work transition. So schools would pay me and I had a team of other speakers that grew over time to go in and run these programs, and at the end of the programs we do these surveys with students, and so it was a really sort of symbiotic relationship where we were able to add value at schools and colleges and then also get us, you know, put our finger on the pulse of what's happening in all these different communities.

Speaker 2:What students were expecting and thinking and so that was how it was funded was essentially was part of what we were doing in schools, and it was slow going. I mean, schools are great once you're in, but they're very they're very heavily networked. So it's hard to get known in the schools world Once you're known, they all talk, and so it was a very slow burn to get started. So anyone who's listening, who's in that like startup zone and it's like trying to make ends meet month after month, I get it. That was the first. You know it's six or 12 months and we were just first early married, like it was. It was that time where it's like, well, is any time to do it? That is a good time to do it, but it's also a tricky time. So it was very much that bootstrapping startup stage.

Speaker 1:So did you yourself come up with the idea of interviewing these students to find out how they were thinking? Was that your own idea or did somebody? It was.

Speaker 2:Yeah, so the process to get into this was interesting. So I had this idea of doing some research around generational change and maybe doing some writing, and I'd always been interested in the speaking writing world, even as a young person I was. I love listening to great communicators. I remember going to a couple of conferences for my parents' work because the babysitter fell through and just sitting in these events listening to people present and thinking that's, I'd love to do that, that'd be awesome. So it was always on the radar and so when I was looking at how, what, what, what could I do to sort of be of value in that space and do something that will be fresh and new and relevant? The generational things obviously was a starting point because I was young. So I'm like I can't be an expert in March at age 22, but I can be an expert in being young because I am. And so I'd written the first draft of a book basically looking at generational differences. What it lacked was the on the ground stuff. The on the ground, you know, speaking to the young people themselves and you sense of what's happening, having primary research data, and so I'd given it to my dad to read. So my dad had been a guidance counsellor in a high school for 20 something years and he said there is such a need for this. You could actually run these programs in schools and then bulk onto that some research of the young people as you're doing it. So he'd had the idea, and so it was one of those sort of moments where I could have gone other way. So he read this manuscript, had that idea.

Speaker 2:Six days later, no notice, passed away, heart attack out of nowhere, fit and healthy, 51 years of age. But two days before he'd passed away, he sent one email to a woman who is the head of the Careers Guidance Association of the state we live in and just said I just want to introduce my son to you. He's written some stuff that could be useful in schools. So after the funeral was done and all the dust has started to settle, I remember like open my email, got back to work.

Speaker 2:In the email was there from him introducing me to Lynn Camp was her name, and so I thought I may as well give it a shot, almost to honor him. I'm like he's gone to the trouble to set this up. It's almost in and one, since the last thing he's left is his email intro and so I emailed her. She was kind enough because I think she was feeling sorry for me to have a meeting and she helped me get started and like that's, that's where it all began. So it's it's a very special thing, because it was such a thin thread that could have gone either way. But yeah, so much of that was from that pivotal experience.

Speaker 1:So what was it that you were doing that your father thought would be helpful to other people? What was it that you were doing?

Speaker 2:Well, he was. So the book that I'd initially written was all about how baby boomers and Gen X is different from millennials, and it looked at the historical context. So what are the things that happened in the formative stages of each of those generations? That was, you know? That meant they had a certain paradigm or worldview, and how did that apply to the way that they were working? So he said the tricky thing we're seeing is we're sending students out into the workforce after school and they might have the knowledge that they need from school, but if I don't know how to for want of a better term play the game, understand how their bosses are thinking and how to work with others who are from a different generation, that's where. That's where they're falling down.

Speaker 2:And he said there's government funding to help with this sort of stuff, to help students make that transition from school to work. He said this material fits into that funding model beautifully. It's exactly what schools are being asked to provide to students. No one much is doing it. Knock yourself out, give it a go. And so that was what I think you saw was valuable. Was that the thing that students weren't getting at school at the time?

Speaker 1:And what did you find? What were they not getting?

Speaker 2:I think the big thing and it's funny because you sort of hear the trope that young people are all and then you fill in the blanks disrespectful, lacking work ethic, with the rest One of the things that was pretty clear was there was a sense of ambition and enthusiasm with Generation Y or the millennials, that if it didn't present well, if it didn't present with humility, came across as entitlement and presumption, and so a lot of it was saying when you go into the workplace, you need to recognize that your natural zeal for wanting to take on new roles and ideally, be a leader soon, and that ambition can be perceived as being precocious or entitled If you don't also go in with a posture of openness, of like, I want to be mentored, I'm keen to learn, and so I try to understand and looking at what we're seeing with Generation Y in terms of what do they expect from a pay packet perspective, what do they expect?

Speaker 2:And so how quickly they've been leadership, and so you think, wow, that's so naive. But it was a function of a generation who grew up in the era of self-esteem, where they were told they could be anything they wanted to be, do anything they wanted to do, and so you wanted to make sure that they went into the workplace, not that in a way that that would get squashed, but also they went into the workplace with a realistic expectation and an ability to go in and learn and not be, not essentially get a one's hackles up straight out of the gate by being a young, precocious, wanting to run the show tomorrow, type thing. That's what we saw is just some of those mismatches and expectations that were a function of the era that Gen Y or that millennial group had been raised in.

Speaker 1:So that sounds fantastic. And how did you move from that to your next project, which was more about like stubbornness and how to persuade people that sort of stuff? How did you move?

Speaker 2:So each of the books has basically been, I guess, the next step. You know I'm often asked a question of how do you come up with ideas for what you write about? And typically I just listen, like if you listen well enough, your clients will tell you what they need. Your clients will tell you what's frustrating them and being difficult for them in their roles. So initially I spent a whole lot of years doing this generational stuff. So I wrote three books around that whole bridge in the generation gap discussion, and then I realized that this is only part of the equation. There's a lot more going on.

Speaker 2:If you just sort of scan out one or two steps from the generational piece, the broader context is societal attitudes are changing and technology is moving fast and consumer expectations are changing. There's a whole other that's happening around this and in some ways the flywheel has been kicked off by generational change. Now a lot of these things are happening because younger generations are coming through using new technologies, having different expectations, and so gradually that becomes the norm. And so, looking at what was happening more broadly, so the next three or four books looked at this question of where's the world heading, how do you get ready for change.

Speaker 2:How do businesses that stay at the cutting edge over a long period of time do that? So how do you not become the Kodak? The sea is the blackberries of the world. You know what do those businesses do wrong? How do they not pick what was coming or identify the trends before it wiped them out? And then, having done a lot of that work over the last probably the last 12 years, has been mainly focused in that space. Again, the question was consistently I get it, I know what's coming now, I know what we need to do, but I can't get my team on the journey. So that's where the persuasion psychology of stubbornness material came from. I was just seeing that consistently coming up with clients.

Speaker 1:Was there? Was there any particular person or client that kind of triggered this interest in stubbornness?

Speaker 2:That's a great question, not a particular client, but I can think of a few conversations. I remember one particularly was at the Hilton Hotel in Sydney, downtown Sydney. There was a woman there who was running a fairly large team for one of the banks and she you know, when you speak to someone and they're not just frustrated, they are frustrated their whole body. She was so exasperated. She said I've been trying to get my team to embrace I can't even remember what the new technology platform was, was something new that they needed to do. And she said, if we don't do it in the next six months, like we are dead in the water. But she said they just won't. And I've given them all the reasons, all the logic, I've done PowerPoint presentations and videos and but they just not going along for the journey.

Speaker 2:And I remember that and that was probably I don't already had the idea to write this book at that stage, but that was one of those moments. I'm like this is a felt need. It's not just wouldn't it be nice if we could give some people some tips and tools? It's like this is stuff that's actually keeping people awake at night and making their lives very difficult, and that sense of exasperation. I do remember that being a very pivotal moment. Early on that I thought I really I definitely need to write this book next, because I was seeing those same sorts of things come up time again and I think to just realizing a lot of what we've been told for so many years. It's sort of not true. You know this notion that everyone's inherently afraid of change. That's a natural human thing to be afraid of change. And yet some of the more interesting research I came across in writing the book was that it's actually that's not true. We're not afraid of change. What we're afraid of is loss and so if you underpin.

Speaker 2:What is it that? What's the fear of? What's the loss associated with change? Rather than trying to dress the change up or upsell the change, you've got to lessen the loss, try and make the loss feel manageable or not threatening, or at least the choice of the person that's engaging in it. And so things like the loss of the loss of certainty, the loss of power, the loss of dignity, typically when people are digging their heels in, it's that fear of losing one of those things that stop in them changing. And so, rather than trying to push harder or give more evidence or logic, understand what the law says and address that. And that's so often that that's enough in and of itself to shift the game.

Speaker 1:I think that's incredibly true. I think that is so true, yeah, that that really resonates with me. You mentioned before that was it one day when your parents couldn't get a, couldn't get a baby sitter they took you. Is that sort of the most vivid memory of your childhood, or are there some other ones that kind of stand out that you think sort of made a difference in terms of your career choice?

Speaker 2:That's a great question, I think. Certainly I remember that that day that conference was very, very vivid. I remember it was always eight. I remember I was eight, maybe nine, but I think I was eight years of age. And this conference is, there's a woman speaking from the States who was actually speaking and it was speaking about personality styles and she just captured this audience and it was just it was. It was not high grow academic, it was just very accessible but very well researched. She was funny and engaging.

Speaker 2:And yeah, I remember just thinking. I remember saying to mum and dad as we were leaving that day, that's what I want to do. And so they of course the polite parental response yeah, that's nice, yeah, cool. You know, you just assume it'll be nice, it'll be in the same category as being a fireman or an astronaut, but it's stuck like it really did and it was sort of just something that that's funny when I speak to people.

Speaker 2:In fact, we're having a New Year's Eve party this year and I was catching up with some friends yesterday. We're talking about the theme for this news new year's Eve party and the theme is going to be come with what you'd like to be when you grow up and they all laughed and said you're the boring one, because you'll just come as what you are. Because, like it is so true that I just I feel like this is all I've ever wanted to do and I love it, and I realize what a privilege that is and how rare it is, yes, yes, to be doing what you love and to know that, like a couple of close colleagues, their biggest frustration is they just they're like turning 40. And they still have no idea what they want to do when they grow up.

Speaker 2:I can I just the inner angst that causes and I feel so deeply for them because I'm like I don't know how to, how do you help someone figure that out? That's got to be a journey. They go on to a large extent on their own, but I just I can't relate in the sense that I've known since I was really young exactly what I wanted to do and I've had like the crazy privilege of being able to do it and I've worked really hard. But also there's favor, there's luck, there's good timing. I mean I would never assume it's just all, of course, my cleverness that I've fallen into this. So, yeah, I just I love what I get to do, and it really was probably from that age, that age eight, that it was on the radar for me.

Speaker 1:What, what was it about that woman and her speaking that sort of made an impression on you.

Speaker 2:It's a great question because I can't remember anything she said. I mean obviously so long ago. I remember she was wearing a bright blue dress. Isn't it funny the things visually that stick with you.

Speaker 1:Yes yes, yes.

Speaker 2:The sparkly sort of dress. I think Her name was Florence Littower, that's her name. She's been she passed away, I believe, only quite recently, but she'd been a speaker for decades and she was just a masterful communicator. You know, that whole that ability to hold a whole room in the palm of your hands without high energy, without any rara, just by being having a magnetism, and there's something about that that has just, it's always been my goal is to have that ability to influence people from a platform without being larger than life, because I'm not like I'll be on the stage in front of 20,000 people and I'm like it's just like this, like I'm just having a conversation, and there's something about that that I just find from, at least for me and for my tone works the moment I try and speak it up, and it's bigger than it is Like there's insincerity, that just means the audience doesn't connect.

Speaker 2:And so I remember she did that beautifully. There was just, it was just very real, very compelling, very funny, and that made a huge impact. And so that was certainly the way I wanted to do that sort of thing, if and when. So like at age eight I didn't know what that would look like, but all through school. If there was ever a need to get up and do something at a school assembly, I was happy to do it, like I was just always curious about having to do stuff up front. Speaking wise and I'm not a massively extroverted person, I wasn't like the life of the party type human, but in that role I was happy to step up and so I think I feel like I'm built for it. In many ways it's just a very natural skill fit.

Speaker 1:Aha, wonderful, wonderful. I mean it's great to be in a position to say that I'm happy with who I am Like. Yeah, you're totally happy in this skin that I'm living in right. Yeah, that's so few people. So few people attain that position in life. Yeah yeah, yeah. So you are very, very lucky and I congratulate you and I hope it keeps that way for a long time. You're not ending, we are not ending. I'm just putting it in there. Are you presently in an intimate relationship?

Speaker 2:Yes, yeah, I'm married. My wife and I have been married, for I think it's going to be 18 years next year, so that makes us feel very old. Yes, but yes, 18 years.

Speaker 1:Don't talk to me about old. I'm old relative, isn't it? I'm ancient. So what does your wife do?

Speaker 2:She's an lecturer at a university. She teaches drama, hedda Godji, so how to teach, or how to use drama to teach, and also drama history, theater production. So she teaches in the dramatic arts faculty and then also runs a theater company of her own. So they're putting on productions, live theater productions, every sort of three or four months, so she's got a pretty full plate as well.

Speaker 1:Yeah, do you have it? Did you say you had two children?

Speaker 2:Just the one, yeah, one little seven year old.

Speaker 1:Seven year old. Yeah, would you like him to follow in your footsteps?

Speaker 2:Not necessarily. I have no desire that he would. He's not the same temperament as me. He's much more like my wife, so I would be surprised if he was attracted to.

Speaker 1:What does that mean?

Speaker 2:What is she like? She's certainly more introverted than I am and for me I'm a very linear, logical, sequential thinker which I feel like for what I do is a real asset For writing books and crafting content. To deliver on stage it really helps. My wife is far more creative. She's just much more take things as they come. She's still very structured and organized to get things happening. She produces life theory. You've got to be pretty organized to do that. But she's less linear than I, am far more creative and I think our boy is the same.

Speaker 2:So I'd be surprised if he was attracted to the sort of work I do. But hey, you never know. But it's interesting seeing him, even as a young child, being able to see what I do and for him to sort of get it like he came to a conference recently and just sat in the audience and he just sees me at home just being dad and then suddenly seeing me in that role was just a bit of it was an interesting moment for him and just the privilege it is for him and I think he's aware of the privilege to an extent of just the experiences he has because of that. So today, like it's school holidays here. So when we finish this chat, I'm taking him today to a colleague of mine's workshop.

Speaker 2:This is one of us straight is leading robotic engineers. He's a 35-year-old guy, like a proper genius, designs robots for people with disabilities, like designed a car for someone who couldn't move arms or legs quadriplegic, but they can drive it while you're moving their eyes and he's invented all this technology. Anyway, I said to our little boy, I said do you want to go meet the man that builds robots? And he said I'd love that. So we're going over today to meet this guy. So just, I think our little boy is so aware that just because of what I get to do, he gets to meet some really interesting people. So you know, you never know what your kid will do. But I think part of the job as a parent is just to expose him to as many different people and ideas and ways of thinking, and hopefully something a bit like me as an eight-year-old in a conference convention center grabs their fascination and that becomes a seed of an idea. So that's the hope.

Speaker 1:If you could have dinner with any three people, dead or alive, who would you choose?

Speaker 2:I think Winston Churchill would be fascinating. Yeah, matt McGandy would be another one. I would love to just learn from you know what's the sort of mindset you have that allows you to do what he did. I think Steve Jobs would be really interesting to speak with as well. I just think he'd be his take on things, and even looking at what Apple has done over the last you know, the years since he passed away, I often think what would Steve do, and so I think those three would be people all very different people obviously, but they'd be people. I've read their biographies. I find them interesting as humans. I'd love to see what they're like one-on-one.

Speaker 1:I have just finished a wonderful book. I think it's one of the best books I've read in a long time. It's called Checkmate in Berlin. Have you heard of it? I haven't. No, it's an amazing book. It deals with sort of the last few months of the Second World War and then sort of what happened in Berlin, with the Russians and the Americans and the Brits and the France coming in and taking it over. But the reason I mention it is because Churchill, after the war, was the only leader of the Western world who saw what Russia was up to, and he's the one who coined the phrase the iron curtain.

Speaker 2:Did he really? I didn't know that.

Speaker 1:Yes, when he was out of power, when he was already voted out. But he was asked to speak in the United States at some small Midwestern university and he made this incredible speech where he said iron curtain is descending from Warsaw to, I don't know, bulgaria or whatever. Yes, and everybody attacked him for it. Wow, kind of nonsense is this, you know. And boy did he see the world how it really was, and everybody else was just denying what Stalin was really up to, and Churchill was the one who saw it coming, and he was the one in 1939 who was, of course, seeing what Hitler was up to. Yeah, right.

Speaker 2:So yes, I'm definitely for Churchill, yes, I'm a great I wonder what he'd say of the current state of play globally at the moment, because I think the beauty of someone like Churchill is he had that ability to sum up complex situations something pithy, memorable, repeatable and like, devastatingly accurate, Like some of his phrases. The terms of phrases got cut through and you couldn't ignore them, and I wonder what he would make of some of the things that we dress up in so much language today. He'd just speak through that, I suspect, in a way that would be probably quite useful.

Speaker 1:Yes, I think so. Well, where is Churchill now, when we need him, right? Yeah, yeah, yeah. What would you like to be remembered for?

Speaker 2:That's a great question. I think the thing that I enjoy hearing the most like if I ever hear the feedback that I've been kind to people. I love that and because that's something that I'm very mindful of, particularly now that in the position I'm in certainly in the industry that I'm in typically I'm sort of whisked into back rooms and green rooms it's easy to just float around and not have to engage with people and not make people feel seen and valued, and I tried to not do that. I could try to every person, whether it's a sound technician or someone backstage just taking a moment, to be kind and valuing them. I try and remember to do that consistently because it's easy to forget that, and so I think that's the thing when I hear the feedback, that's what people appreciate. That to me, is like that's the best feedback. So I'd love to think that was the impact.

Speaker 1:Okay, we are running out of time, so one more question.

Speaker 2:Yeah.

Speaker 1:What does being human mean to you?

Speaker 2:Oh, that's a great question as well. I think growing, I think being human is about growing. The moment you stop doing that and you see that. And it doesn't have to be an age-related thing. You meet some people in their 20s and they've decided they've figured everything out about the world and they're not open to growing and changing, and I think what a sad thing. That's the point of being here.

Speaker 2:To listen and learn and grow and change. The moment you stop doing that. I mean, it's that pithy old sort of 1980s saying you're either green and growing or ripe and rotting, and I think there is some truth in that. If you're not growing and changing, what are you doing? If you're not going forward, you're going backwards, and so that's probably the core of what it is to be human is to be always open and learning new things and things you hadn't considered before. And I guess that's probably part of the heart behind this book too is to help people develop a posture where they're able to do that again, To not feel like things that are new are threatening, but things that are new and different can be an opportunity, even if they're uncomfortable or inconvenient truths. Actually, that's how we grow as humans. There's a joy, there's a life in that.

Speaker 1:Yes, and curiosity, you know, yeah, absolutely Not being afraid to ask questions, definitely, which you have done all your life. Well, michael, we are out of town, out of town, out of time, out of time, but we could talk for many, many more hours. It has been a tremendous pleasure. I've been speaking to Michael McQueen and look for his latest book that's coming out when it?

Speaker 2:should be out early December.

Speaker 1:So it'll be all in all the bookstores.

Speaker 2:There's a website. Up a website too.

Speaker 1:That's a great gift for Christmas, right.

Speaker 2:That's it, and thank you for writing an endorsement. That was so kind of you to do that. I really appreciate it. It was a pleasure.

Speaker 1:So the book is called Mindstruck Mastering the Art of Changing, and my guest has been Michael McQueen. So let's stay in touch, michael. I'd love that. Thank you so much for making the time. Take care Until next time. Bye-bye, look forward to it. Cheers, bye-bye, cheers.